This article originally appeared in The Asan Forum on April 29, 2016

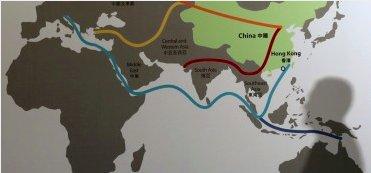

In China’s history, every so often a fever grabs hold of the public imagination. Since Xi Jinping enunciated the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, over one million academic papers were written in China on this new subject.1 China’s experts were recruited to celebrate Xi Jinping as the “designer of China’s road to being a great power.”2 BRI is also known as the “new Silk Road” and aims to connect China with Europe through transport corridors overland across Central Asia as well as by sea around the Asian landmass.3 The BRI is touted as covering two-thirds of the world’s population and according to official Chinese media will account for one-third of global gross domestic product (GDP). The new Silk Road is an extremely ambitious initiative that aims to reshape the current geopolitical landscape.

Silk Road fever, however, took longer to seize European attention.4 The BRI as a top down initiative left many Europeans asking what it meant, what it was for and what were the projects proposed. Their Chinese interlocutors could not answer at first and were initially frustrated by the lack of enthusiasm shown by their European counterparts toward their Silk Road Dream.

China Marches West

While China was developing the BRI, American attention was focused on China’s Eastern borders. China had shown increasing assertiveness there and advanced its claims to the East and South China seas. It declared an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the East China Sea in 2013 and proceeded to create island outposts over a vast expanse of water in the South China Sea, challenging the claims of its neighbors including the Philippines and Vietnam. Beijing undertook an ambitious island building program on seven features in the South China Sea literally changing facts on the water and building a great wall of sand at sea.5 While all this was going on to the East, China was also launching the BRI to expand its influence westward.

Transport Corridors

Centered on transport and energy infrastructure, the BRI seeks to create a transport corridor linking China to Europe overland via Central Asia and another linking China to Europe by sea. For instance, part of the overland corridor is the Yiwu-Madrid Railway line, the world’s longest, which connects China with Spain spanning 13,000 kilometers in 21 days.6 Both the overland and the maritime corridors are meant to stimulate economic development along the way. The overland “Silk Road Economic Belt” also includes a USD 46 billion-infrastructure program in Pakistan to build, among other things, a new railway line and new coal-fired and hydro power plants. The two corridors are meant to expand China’s trade to the west, creating markets for its heavy industry and construction companies, to help ensure China’s energy security and to extend China’s influence through its investments. Therefore, they have strategic as well as economic implications.

From the technical point of view and from the point of view of financial viability, the overland transport corridor presents some challenges that are seldom addressed: railways and roads across mountain ranges and deserts are expensive to build, and it is difficult for trucks and trains to compete with sea transport when it comes to economies of scale. At present, over 90 percent of trade between Europe and China is seaborne. However, the Chinese emphasis is on the rail and road links as symbols of connection, on the associated local economic development, and most of all on the end goal or destination of the transport corridors. China speaks of Eurasian integration (yaou or Asia-Europe integration from the Chinese point of view). The end goal of both the overland and the maritime corridors is Europe.

New Banks for a New Silk Road

To fund the infrastructure projects linked to the BRI, China has established a Silk Road Fund of some USD 40 billion. It has also established a new bank, the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which European countries have rushed to join despite US antipathy, eager for business opportunities. Fourteen of the 28 EU member states are now members of the AIIB. China has already carried out sizeable infrastructure investments in Europe, notably in Serbia, a country that is not yet part of the European Union and where infrastructure construction standards are therefore less stringent.

Market Economy Status

For China, 2016 is an important year as it is now the time they long have anticipated of “automatically” receiving market economy status (MES) based on the 2001 terms of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). According to Chinese diplomats in Brussels, this is now the most important issue on China’s EU agenda. Despite the 2001 agreements, granting China MES is not automatic under EU law but requires specific legislation. There is debate now within the European Union about whether China should be granted MES or not, with certain EU member states fearing Chinese dumping practices.

China’s Economic Statecraft

Economic statecraft can be defined as using economic resources (e.g., foreign aid, trade sanctions, or strategic investments) to influence policy decisions in other countries. China attempted to apply economic statecraft to achieve a favorable outcome for MES through the pledge of BRI funds for the European Union’s European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI). EFSI is the investment vehicle for the European Investment Plan or “Juncker plan” from the name of the current European Commission president. With a budget of EUR 315 billion, the “Juncker Plan” is to fund key infrastructure projects and help kick-start the European economy.

In June 2015, China announced its intention to contribute 5 to 10 billion euros to the EFSI.7 The European Union and China subsequently set up an EU-China Connectivity Platform to link infrastructure investment under the BRI with that under the “Juncker Plan.” The Connectivity Platform was designed in part to bring transparency to China’s investments in Europe. Currently, information about Chinese investments is jealously guarded by member states. China’s financial pledge appeared in the Chinese media and was featured prominently on the website of the Chinese Mission to the European Union. However, EU officials decided not to accept China’s pledge until all the details were worked out on the technical aspects of the fund.

In early 2016, with the eruption of protests against granting China MES and lack of clarity on where the European Union stood on this issue, the promised Chinese financial pledge morphed into a mirage. “It is being held hostage to MES,” one well-informed source told me. This instance highlights China’s efforts to use economic statecraft to influence policy decisions in the European Union and advance China’s strategic objectives.

Beijing attempts to exert influence in particular towards the eastern part of the European Union, which has a greater need of Chinese investment. China has already established a special forum to deal with the EU Eastern Member States and applicant countries, the “16+1.” The forum has its own secretariat within the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs that organizes regular meetings. Countries that do not criticize China on human rights and that support China’s policies are rewarded with investments but also with visits of Chinese leaders, as was highlighted by the recent visit by Xi Jinping to the Czech Republic (although the visit also coincided with widespread protest against China’s treatment of minorities including Tibetans).

China’s economic influence has also been brought to bear on other members of the European Union, including the older, larger member states. For example, in the last few years Britain has behaved in a way that has been defined as “meretricious” because of its courting of Chinese investment and silence on human rights. China has also made considerable investments in the Piraeus Port in Greece as well as in Spanish ports. As all major partners of the European Union do, China lobbies each EU member state separately to shape policies at the EU level in a way that suits its goals.

With the European Union strained under multiple crises, one wonders whether China’s efforts to shape individual state behavior will contribute to the further erosion of EU institutions at a time of great stress. Is it in China’s long-term interest to have a united or a fractured Europe?

China’s Answer to TTIP

China’s BRI can also be seen as a response to the US Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and particularly the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) initiative. Negotiations for the TPP, which aims at trade liberalization and economic integration among twelve Pacific countries of the Americas, Asia, and Oceania, started in January 2008 (the agreement was signed in February 2016 and awaits confirmation by the US Congress). Negotiations for the TTIP, which pursues similar goals between the United States and European Union, were launched in February 2013. Xi Jinping announced the BRI just a few months later. Through the BRI, Beijing hopes to boost connectivity with the European Union, the largest market in the world, and to lay the foundation for increased trade and economic integration. Eventually, China hopes to conclude an agreement on a free trade agreement (FTA) with the European Union. However, before that is possible, China must conclude a pending Investment Agreement with and obtain MES from the European Union.

Paradox of Connectivity

At a time when some European member states have suspended Schengen (free movement of people inside the European member states) and are building walls of razor wire along borders, the concept of increased connectivity may not find fertile ground. Connectivity is not always seen in a positive light. Popular concerns about waves of migrants moving to Europe in the millions has created a situation where walls are going up, rather than coming down.

In addition, many EU member states are concerned by competition from China and the economic fallout and job losses that will result if China is granted MES. Some disgruntled observers have described the “One Belt One Road” as “One Belt One Way (OBOW).” The train route from Yiwu to Madrid demonstrates OBOW. More than half of the rail cars used to import Chinese products to Spain needed to be shipped back to China, as there were not enough Spanish products to export by train. Part of China’s challenge is to convince Europe that connectivity is a win-win not just a faster way to dump goods on EU markets.

A Bumpy Road Ahead?

Although this article has focused on the European end of the New Silk Road, there are multiple challenges Beijing faces across Central Asia. The question of regime change in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, stability in Afghanistan, Russia’s role in the region, and the growth of militant Islam will test China’s Silk Road fever. The BRI has raised huge expectations, and there is a definite risk that it could over-promise and under-deliver. Despite these difficulties and despite the recent economic slowdown in China, the BRI is likely to be continued. The Chinese leadership and Xi Jinping himself are personally associated with it and cannot lose face. There is a danger that economic decisions in Beijing will take a back seat to political ones, and this may increase the risk of financial overstretch. If fewer funds are available, China may try to enlist the support of others to help fund the infrastructure projects which are foreseen by this initiative, for instance through the AIIB. China’s Silk Road initiative is likely to remain an important tool of Beijing’s economic statecraft towards Europe in the years to come.

1. One Belt and One Road” (yi dai yi lu) and “Belt and Road” appear in official CCP documents. As Min Ye has pointed out in her previous essay, “the belt, the road” is a preferred phrase. After listening to many Chinese academics and officials wince at the abbreviation “OBOR,” I use the more desirable and official phrase of “Belt and Road Initiative” and the acronym BRI in this paper.

2. Youth.cn, http://news.youth.cn/wzttt/201502/t20150227_6493571.htm.

3. For background on this topic see, Theresa Fallon, “The New Silk Road: Xi Jinping’s Grand Strategy for Eurasia,” American Foreign Policy Interests: The Journal of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy 37, no. 3 (2015): 140-147, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10803920.2015.1056682.

4. Although this article does not highlight Europe, it is important to point out that there are some cautious voices inside China too on treading carefully along the Silk Road. See, Shi Yinhon, “China must tread lightly with its ‘one belt, one road’ initiative,” South China Morning Post, August 18, 2015, http://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1850515/china-must-tread-lightly-its-one-belt-one-road-initiative.

5. Jeremy Bender, “Top US admiral: China is building a ‘great wall of sand’ in the South China Sea,” Business Insider, March 31, 2015, http://uk.businessinsider.com/us-admiral-china-is-building-great-wall-of-sand-2015-3?r=US&IR=T.

6. Stephen Burgen, “The Silk Railway: freight train from China pulls up in Madrid,” The Guardian, December 10, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/dec/10/silk-railway-freight-train-from-china-pulls-into-madrid.

7. Robin Emmot and Paul Taylor, “ Exclusive: China to extend economic diplomacy to EU infrastructure fund,” Reuters, June 14, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-china-exclusive-idUSKBN0OU0H820150614.

8. “16+1” includes 11 EU countries: Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and five EU candidate countries—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, FYROM [Macedonia], Montenegro, and Serbia.

9. For more information on the “16+1” see, Theresa Fallon “China’s Pivot to Europe,” American Foreign Policy Interests: The Journal of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy 36, no. 3 (2014): 175-18

10. “Chinese President Xi Jinping arrives in Prague amid protests,” DW, March 28, 2016, http://www.dw.com/en/chinese-president-xi-jinping-arrives-in-prague-amid-protests/a-19147019.

11. “US attacks UK’s ‘constant accommodation’ with China,” The Financial Times, March 12, 2015, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/31c4880a-c8d2-11e4-bc64-00144feab7de.html#axzz46g0gaxTv.