07/05/2021

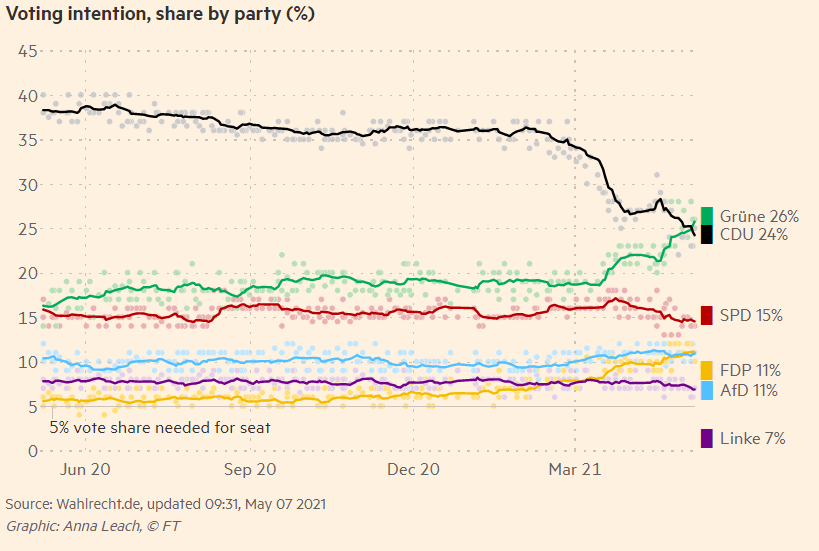

On 26th September 2021, the 16-year era of Angela Merkel’s German chancellorship will come to an end. The race for her succession is already in full swing, and according to the latest polls, the current lead goes either to Merkel’s Union of Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) , attracting between 23% and 28% of the votes, or to Alliance ’90/The Greens (hereafter “the Greens”), casting an estimated 21-28% of the votes. Even though the current numbers show significant variation and need to be read with a certain degree of caution, the overall poll development shows that the Greens have emerged as a serious competitor for the chancellery in Berlin.

The points represent polls and the lines represent weighted averages.

In early 2021, the green party itself had already clearly expressed its ambitions to win the election, a claim that has been reiterated frequently ever since, most recently when Annalena Baerbock has been presented as the Greens’ official chancellor candidate. Irrespective of potential coalitions to be made, if the Greens manage to uphold or increase their poll ratings at the national elections, they will inevitably play a central role in the formation process of the next German government, possibly even aiming for taking the chancellorship. With this in mind, questions regarding Germany’s future political trajectories arise. However, instead of focusing on domestic developments, this piece will turn to the potential implications of a Green chancellorship on the European Union, and, more specifically, its foreign policy and stance towards China.

What to Expect from the Greens’ China Policy?

In their recently published preliminary election programme, the Greens, in accordance with the EU´s Strategic Outlook on China, consider China simultaneously as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival. The specific abstract on their planned China policy entails little surprise in terms of content, with the Greens mainly seeking to balance their criticism on human rights violations (cfr. Hongkong, Xinjiang, Tibet), with the call of a “constructive climate dialogue” and a mandatory due diligence supply chain law in the EU.

Considering that the Greens have already introduced a Xinjiang-related motion in the German “Bundestag” and openly requested Merkel to address recent developments in Hongkong when meeting Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, it is to be expected that this rather tight stance towards China will become more clearly reflected in upcoming discussions on the EU’s China policy. In particular as the European Greens/EFA Group were the ones to initiate the recent European Parliament resolution on human rights violations and forced labour in Xinjiang, paving the way for international sanctions to be imposed on Chinese officials in March 2021. A green victory in Germany would thus provide the European Greens/EFA Group with high-level backing from Germany.

The End of the “German Engine” in the EU?

In addition to what needs to be prioritised on the agenda, the Greens’ preliminary election programme also entails a preview on how the party seeks to engage with China. The Greens clearly plan to elevate bilateral relations with China to the multilateral level, to be closely coordinated with the EU Member States, as well as the US. While both the need for European unity and a marked role for the US in EU foreign policy were already included in the Greens’ 2019 European election programme, the explicit reference to the US in the context of EU-China relations is a novelty.

If implemented effectively, the Greens’ more inclusive and coordinated China approach would constitute a major shift to Germany’s current role in EU-China relations, which stands for a rather centralised policy making. Latest evidence can be found in Angela Merkel’s impact on the conclusion and negotiations of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), which she personally helped to push through at the end of December 2020, just before the end of Germany’s EU presidency. Merkel’s initiative to conclude the negotiations in such a rush evoked criticism among other EU nations and officials, expressing their dissatisfaction about Germany’s dominant position in the EU and the lack of sufficient participation. According to POLITICO, some officials said they felt “steamrolled by Merkel and the ‘German engine‘ inside the European Commission”.

This ‘German engine‘ alludes to the amalgam of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, her Chief of Cabinet Björn Seibert, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Michael Hager (Chief of Cabinet of European Commission Executive Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis), as well as Sabine Weyand. The latter, as Head of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Trade, has been in a leading position in the negotiations on the CAI with China. Apart from their nationality, all five also share the same party background, either holding official positions in the CDU/CSU or, like Weyand, being closely affiliated with it.

Another driver behind the CAI is said to be French President Macron, who reportedly managed to secure benefits for selected french enterprises such as Airbus under the agreement. This motivated Poland and Italy to publicly criticise Germany and France for rushing the deal over the heads of the other EU Member States, and without coordinating with the Biden administration. Reinhard Bütikofer, one of the German Greens’ representatives in the European Parliament and Chair of the Parliament’s Delegation for Relations with China, later referred to the deal as a “solo run” that does not live up to the EU’s self-aspirations of multilateralism. Further criticism of Germany’s and France’s “2+1” approach towards China was raised by Omid Nouripour, foreign spokesperson of the Greens, who instead called for closer coordination among all EU member states.

However, while some may regard a strong German-Franco leadership as essential when dealing with an economic heavyweight such as China, “solo-runs” like the CAI are unlikely favourable to bring the EU closer together on matters related to China. This rather holds the risk of further fractionating the EU internally, making the Union and especially smaller and less-represented EU Member States more vulnerable to divide and conquer tactics by external actors such as China.

A green German chancellorship, beyond formally disrupting the CDU/CSU-led German engine, may therefore entail the opportunity for enhanced multilateralism and coordination among the EU Member States leading to more inclusive policy-making processes, as well as a more critical and fierce stance towards China. The extent to which such a change can actually be achieved will to a certain degree also rely on the willingness of the remaining members of the “German engine” and the European Commission to leave the status-quo behind once Merkel is gone. The announcement by Valdis Dombrovskis to temporarily suspend the ratification efforts of the CAI over the recent Chinese sanctions against MEPs and other EU officials indicates that the European Commission is at least partially giving heed to the critical voices on the CAI in the European Parliament. As the CAI ratification process continues, it is to be expected that the European Greens/EFA, strengthened by a German chancellor representing similar values in the European Council, will certainly play a decisive role in parliamentary debates and decision-making processes.

From “Change Through Trade” to a “Value-based” China Policy ?

Both the German and the European Greens will face the challenge of pursuing their ambitious climate goals with China as an undisputedly strong and important partner, while at the same time defending their core values, balancing this against approaching China also as a “systemic rival and competitor”. Other areas for possible cooperation (and friction) with China include the EU’s pursuit of strategic autonomy, cyber security and EU-China security cooperation.

In the EU’s interaction with China, the Greens’ MP Jürgen Trittin therefore suggested adopting a “value-based realpolitik”, according to which Chinese progress in certain areas should be recognised, whereas its shortcomings in other aspects should be identified and addressed. Annalena Baerbock, who like the co-chair of the Greens, Robert Habeck, is considered a “realo”, recently admitted that while “decoupling” from China as a major economic power would be difficult, a stronger position when defending European values vis-a-vis Beijing would be envisaged.

The combination of a clear, values-based stance towards China with continued cooperation would represent a turn-away from Angela Merkel’s “Wandel durch Handel” (“change through trade”) policy, which assumed that with China’s economic opening, a political opening would follow as a by-product. Recently, Merkel’s policy has been criticised as “disproved” by Nils Schmid, foreign policy spokesperson of the SPD, the Union’s current and the Green’s potential future coalition partner. Schmid further added that there will be “a more robust approach to China after she [Merkel] goes”.

Support for a more assertive position towards China was also voiced by the Liberals from the FDP, the possible third partner in a Green-led coalition. Despite China’s economic importance, party-leader Christian Lindner warned against limiting the relations with China on purely economic issues – as set forth by the “Wandel durch Handel” policy – instead demanding Germany to stand up for its own core values when interacting with the Chinese side. Likewise, Bijan Djir-Sarai, the FDP’s foreign policy spokesperson, called on Germany and the EU to overcome the “naïve” thinking that economic interaction would automatically lead to a political opening of China and move toward a more realistic and better defined China approach.

What about Feasibility?

Whether a compartmentalised, value-based China policy will be feasible to be maintained is at least to be questioned. First, the recent tit-for-tat sanction exchange between the EU and China shows that embracing China, as embodied by the agreement on the CAI, and criticising it simultaneously will not go uncommented by Beijing. This finding is particularly relevant in view of the EU’s and Germany’s trade relations with China. With an overall trade volume of €586 billion in 2020, China has been the EU’s largest trading partner. Overall, the EU exports to China totalled €202.5 billion, with almost half of it accounting for Germany (€95.9 billion). However, while the EU’s trade relations with China should definitely be taken into account when considering a new strategy, China’s overall role in terms of trade and investment still remains “relatively minor, particularly when compared to US actors”. At the same time, the importance of the EU for China should not be understated either. As the world’s largest single market and one of the most important foreign investors in China, the EU not only constitutes an important destination of Chinese exports but also serves as a source for job-creation and know-how. This mutual reliance on a stable trade relationship provides the EU with a certain degree of leverage, which could be used when reframing the Sino-European relationship.

Second, the transatlantic approach to China pursued by the Greens could be jeopardised by its rather sceptical NATO policy. Although the Greens have overcome their radical “anti-NATO” sentiment , Annalena Baerbock’s call for the withdrawal of nuclear weapons and her latest questioning of NATO’s 2% target led to a renewed outcry. However, whether or not the Greens’ NATO position will ultimately impede a closer transatlantic coordination on China remains speculation and will also depend on its coalition partners.

Third, will the Greens be able to implement their political programme, shaped by years in parliamentary opposition, once they would be in a leading government position, with all the consequences that may entail? After all, they will have to balance business and strategic interests on the one side with the moral aspirations of their own foreign policy on the other side. According to Ulrich Speck, “there is a considerable risk that a Green-driven or -influenced foreign policy would be very strong in statements, but lofty on the delivery side”.

Despite the legitimate scepticism on the operationalisation side of the Greens’ foreign- and China-policy, the recent letter of Ursula von der Leyen and Josep Borell to the European Council, in which they voiced their dissatisfaction and concerns about China’s lack of progress on economic promises and its “authoritarian shift”, shows that also the EU’s stance towards China is changing and tightening. A Green German chancellor pursuing a clear-cut value-based realpolitik could therefore prompt a further shift in Brussels as well.

Author: Manuel Widmann, Junior Researcher, EIAS

Photo Credit: Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Nordrhein-Westfalen; (CC BY-SA 2.0)