22/04/2020

The Asia-Pacific landscape has lately been the theatre of further competing hegemonic visions resulting from China’s ‘great power’ status pursuit and the US’ subsequent ‘rebalance’ towards Asia. China’s rise has not only been questioning US global leadership and its role as security guarantor but also enabled China to assert increasing political and economic influence on the Republic of Korea (ROK). While Korean domestic debates began focusing on the country’s prospects among great powers competition, as well as the durability of South Korea’s alliance with the US, the recently resumed ballistic missile activities made a nuclear-armed North Korea return to the spotlight further heightening the precarious security position South Korea finds itself in. In fact, South Korea is seized between two initiatives: China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the US Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP). As principal instruments in attaining their respective geo-strategic goals, Seoul’s choice in favour of one or the other could contribute to shift the tables of the competition and reshape the regional order in Northeast Asia. Indeed, the US has strongly advocated the ROK’s participation to FOIP, but South Korea has only recently expressed its willingness of getting involved due to the challenges presented by the FOIP. South Korea’s first challenge in linking its New Southern Policy (NSP) – designed to strengthen ties with ASEAN – with FOIP resides in the China-containment narrative associated with the FOIP, which further reaffirms Seoul’s strategic dilemma. Additionally, the recently strained US-ROK relations, as well as the ROK’s preoccupation with the North Korean contingency and inter-Korean dialogue add reasons for ROK cautiousness in officially endorsing FOIP language. Moreover, Seoul’s intent in pursuing greater regional autonomy through its New Northern Policy – aimed at improving South Korea’s partnerships with countries located north of the peninsula – and NSP is the cause for ROK’s limited enthusiasm for FOIP.

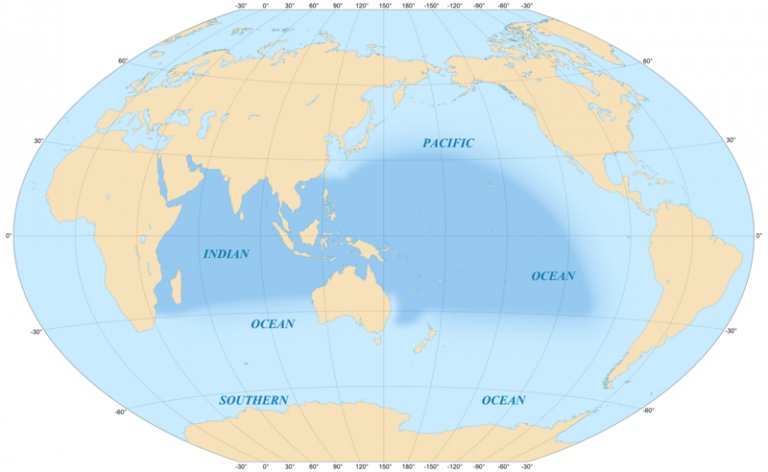

The Indo-Pacific is a geopolitical and security construct of contested interpretation. The geographical space covered by FOIP contains important trade routes that satisfy the (energy) needs of some of the world’s most populous nations. South Korea holds considerable interests in play in the South China Sea (SCS) as the greatest part of her energy imports passes through the area. In fact, it has generally been upholding international law, regional stability, free flow of commerce and dispute settlement through dialogue – all FOIP principles – as potential instability and conflict could block trade routes. Nevertheless, it has no direct strategic or military interests in the SCS. The US has strongly advocated South Korean participation to FOIP as South Korea’s full adherence, as an independent policy actor, would bring political credibility to the ‘vision’ that would attract third countries – consequently fostering multipolarity – and validate an international rules-based system in the SCS and thereby increase US capacity.

However, the US narrative emphasises South Korea’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific dilemma. In fact, it is being perceived that the United States unveiled its own strategy based upon a ‘free and open’ Indo-Pacific narrative as a means to contain China’s increasing geo-economic and strategic influence in the region. Indeed, the 2019 Indo-Pacific Strategy Report explicitly underlines the nature of this China-containment initiative when it states that “the geopolitical rivalry between free and repressive world order visions is the US’ primary security concern in the Indo-Pacific. (…) In particular, the People’s Republic of China […] seeks to reorder the region to its advantage.” Consequently, the US has conducted several freedom of navigation operations to challenge China’s excessive maritime claims in the South China Sea. Seoul’s motivated reluctance in accommodating the US FOIP is exemplified by the 2016 Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile deployment. China retaliated by penalising the South Korean economy with unofficial economic sanctions and President Moon Jae-In had to publicly concede to China’s demands. Seoul agreed to not allow anti-ballistic missile systems in the future, to not participate in any region-wide US-led missile defence system and to elude the creation of an ROK-US-Japan military alliance. Hence, South Korea was strongly discouraged to promptly support any US-led strategy aimed at containing China. Current FOIP language more than alludes to a strategic China-targeted initiative.

On the other hand, if the US continues being reluctant to support Moon’s primary security policy – advancing the denuclearisation of the DPRK and inter-Korean dialogues – South Korea has added reasons for its cautiousness in endorsing FOIP language in its NSP. Indeed, heightened frictions in US-ROK relations pushed South Korea towards China, which could play a vital role in the North Korea denuclearisation talks. As the DPRK’s first trading partner and principal benefactor, China is in a strong position to exert economic and diplomatic leverage on the latter. The stalemate in the US-DPRK dialogue, that has persisted since February 2019, ultimately negatively impacts inter-Korean relations. As the US insists on coordination concerning the North Korean contingency, South Korea has little perceived freedom in advancing independent dialogue and credibly supporting reunification plans. The ROK is especially preoccupied with maintaining momentum since March 2020 has been the most active short-range missile testing month in DPRK history.

South Korea’s intent in achieving greater regional autonomy is also one of the reasons why its Blue House – the Korean President’s official residence – has shown little enthusiasm towards the FOIP Strategy. Seoul is primarily preoccupied with occurrences on the Asian landmass as North Korea remains the core driver of the ROK’s foreign policy. Indeed, since 2013, the ROK has been working on linking its New Northern Policy with China’s BRI to facilitate infrastructure building that would reconnect South Korea to North Korea and the Eurasian continent. Nonetheless, Seoul’s passive role regarding the shifting regional order in the South China Sea could affect its interests in the area in the long-term. Consequently, it could take an example to countries that have formally adopted FOIP (namely India, Japan and Australia) but have been shaping their own narrative rather than accommodating the US’ one. In fact, in June 2019, South Korea announced for the first time that it would “pursue harmonious compromise between the New Southern Policy and the Indo-Pacific Strategy.” However, the joint explanatory document on the improvement of cooperation between the NSP and FOIP, released in November 2019, principally focuses on non-traditional security challenges and provides no information about traditional military and security affairs. Hence, Seoul seems to be trying to accommodate both US’ and China’s demands while showing the real extent to which it is willing to endorse both strategies, utilised by the ROK with the goal of enhancing regional autonomy.

Although the alliance between the United States and South Korea is largely based upon the potential security threat of a North Korean invasion to annex the South, differing priorities regarding the DPRK foster inherent tensions. Hence, understanding of each other’s views can be expanded by increasing legislative and educational exchanges between the two foreign policy communities. Consequently, the US could adopt a flexible approach and support South Korea’s goal of engaging with North Korea before denuclearization occurs. The United States could also reassure its ally that the debated joint military exercises and the number of troops stationed on the peninsula leave its security commitment to South Korea unchanged. Ultimately, enhancing economic cooperation could be a more effective tool in advancing shared domestic objectives and relax tension in security relations.

Author: Giulia Iuppa, Junior Researcher