Moreover, besides the widely anticipated meeting between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin that took place on the sidelines of the summit, this was the Chinese leader’s first visit abroad since the beginning of the pandemic. For Xi, the summit yielded the opportunity to confirm China’s role in the region, while Putin wanted to demonstrate that Russia still holds international clout and is not as isolated as others might wish. However, unfortunately for Moscow, the summit may have proved otherwise.

A Setback For Moscow or an Opportunity For Europe?

The SCO consists of China, India, Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, while Turkmenistan attends its gatherings as a guest attendee. After more than a decade as an observer state, Iran signed the memorandum of obligations at the summit, allowing it to become a full member of the organisation as of 2023. In addition, the procedure to admit Belarus as an official member was approved, while Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Qatar were granted the official status of SCO dialogue partners. The members also agreed to admit Bahrain, the Maldives, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Myanmar as new dialogue partners. This will allow them to participate in a range of SCO activities and enhance cooperation in fields such as trade and investment, energy, and regional security and stability support, without necessarily committing to a full membership. In addition, the Comprehensive Plan for 2023-2027 for the implementation of the Treaty on Long-Term, Good-Neighbourliness, Friendship and Cooperation was signed – an effort to step up and ensure cooperation and trust among the members. Although this marked the SCO’s largest round of expansion and largest group of participants so far, Uzbekistan’s clear intention as organiser of the meeting in Samarkand was to avoid the summit turning into an ‘anti-western’ gathering. However, it can be observed that a number of countries under sanctions by the West have been admitted as members or partners to the SCO. The organisation can therefore be seen as acting as an alternative multilateral platform to other existing international organisations, as for instance neither the EU or the US are part of the SCO.

The summit became incidental to what seemed to be an exposure of both Beijing’s and New Delhi’s unease over the Ukraine war. Hence, what could have been an opportunity for Putin to convince the world that Russia is not isolated and does not stand alone, the summit revealed only limited support for Moscow. During their bilateral meeting, Putin reiterated his support for the ‘One-China’ principle towards Xi and stated to understand China to have potential questions and concerns about Ukraine. This may imply a certain unease on Putin’s side and for China to have its reservations on how the situation has unfolded. Meanwhile, Xi did not openly voice his support, nor officially address the Ukraine crisis during the summit or their one-to-one meeting. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi was more upfront in his interaction with Putin by stating that “today’s era is not of war” – signalling a sense of disapproval of Moscow’s actions. Modi also highlighted that this had already been addressed several times over the phone between the two leaders. This may have been a disappointing setback for Putin in his pursuit of greater support from his closest allies, as the battlefield conditions have somewhat turned against Russia as of lately.

In Samarkand, the fault-lines within the grouping became exceedingly visible. On the eve of the summit, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan experienced violent border clashes. That same week, Azerbaijan and Armenia were on the verge of war due to escalating tensions. At the summit Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi met face to face for the first time since the Galwan border clash in 2020. Yet, there was no informal interaction between the two leaders, a reflection of their strained relationship, especially over their unresolved border disputes. Likewise, the absence of a bilateral meeting between Islamabad and New Delhi also illustrated their complex history. Thus, these long-time rivalries will likely stand in the way for all of them to become closer security allies, or manage to settle their own conflicts in due time. Consequently, this lack of internal cohesion undermines the SCO’s capabilities to foster an effective collective security alliance in the region, which ought to be the organisation’s main purpose.

It also became evident that Russia’s role as a regional power in Central Asia is declining. The Central Asian states have been reluctant to show support for Russia as regards Ukraine, which counts in particular for Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Both Astana and Tashkent have shown support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and have therefore chosen not to recognise the independence of the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics. More recently, Kazakhstan refused to recognise the referendum conducted by Russia in the four annexed provinces of Ukraine. In Samarkand, the absence of bilateral talks between Putin and Kazakhstan’s President Kassym Jomart was another telling contrast. Following the lack of support from its long-standing allies, Putin made an announcement on partial mobilisation to seek support from volunteers. In response the Central Asian states warned their citizens against joining Moscow in its war with Kyiv, another failed attempt to gain greater support.

Yet, Russia found some support in its bilateral meeting with Iran’s leader Ebrahim Raisi, as they exchanged critical views on the United States (US) and Europe – accusing them of illegal actions towards Moscow and Teheran. However, this was inadequate to make up for the value of what other partners could have brought to the table. Following the outcome of the 22nd SCO summit, Russia seems to be scrambling for influence and support in Central Asia again.

Central Asia: Neighbours of the EU’s Neighbours

Central Asia has emerged as a key region for international strategic competition, holding great geopolitical significance for global security. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, Central Asia became a host to complicated security challenges, including border conflicts, political unrest, illegal drug trafficking, and the fight against the so-called three evils: terrorism, extremism and separatism. Since the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan in 2021 the security challenges have intensified, triggering a growing fear for potential negative spill-over effects into the region. On the other hand, Central Asia’s strategic location at the crossroads of historical trading routes like the Silk Road, as well as its richness in natural resources has turned the region into an important gateway linking East and West, functioning as a nodal point for transportation and connectivity and as a key partner for trading.

Central Asia is also of strategic importance to the European Union (EU) as it is located in Europe’s eastern periphery – indirectly linking it to European security. As a result, upholding security and stability in Central Asia is also in the interests of Europe. It is clear that the EU missed an important opportunity after the breakup of the Soviet Union to create an EU-Central Asia Corridor of connectivity. It is only since very recently that the EU started to recognise the strategic and economic potential of Central Asia and strengthened its focus on the region

Over the last decade, the EU has increased its level of engagement in and with Central Asia. In 2019, the EU adopted its new strategy for Central Asia to foster a more “resilient, prosperous and closer” relationship with the region. The Union has also sought to upgrade its bilateral ties with the Central Asian states through its Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (EPCA) with Kyrgyzstan (which entered into force in 2019), with Kazakhstan in 2020 and with Uzbekistan in July of 2022. In November 2019 Tajikistan made a request to upgrade its current Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with the EU. After a bilateral meeting in October 2021 negotiations were scheduled to start throughout 2022. The EU’s relationship with Turkmenistan has been governed by the Integrin Agreement since 2010, focusing on trade and related matters.

The EU has also implemented a set of comprehensive programmes and instruments to exert influence across the security sphere. Since the early 2000s, the EU has set up two large-scale security-focused programmes in the region: the Central Asia Drug Action Programme (CADAP), to provide support in the fight against illegal drug trafficking, and the Border Management in Central Asia Programme (BOMCA) which aims to foster stronger management along the borders. In addition, the annual EU-Central Asia High-Level Political Dialogue has enabled the parties to address security concerns and provided an opportunity to enhance security cooperation.

Yet, the EU has been struggling to maintain a strong foothold in the region. This largely stems from the competition coming from Russia and China. Indeed, Moscow’s historical links with the five Central Asian states have given it a distinct advantage in the region. Seen as its ‘near abroad’, Russia has exerted its influence primarily through two collectives: The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) to deepen economic integration in the region and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) to enhance its role as a security provider. Similarly, China’s early efforts – most notably through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – have boosted deeper economic ties and subsequently made it the dominant economic player in Central Asia.

The Future Engagement of EU-Central Asia Relations

The collapse of Russia’s relationship with the US and its allies, the economic sanctions in place and the strong resistance from Kiev have had a direct impact on the five Central Asian states and their economies, which have proved to be more resilient than expected. However, their dependency has become a major challenge following the exposure of Russia’s vulnerabilities and inability to manage and stabilise its economic and security affairs. Consequently, Russia has become a problem for Central Asia. This has forced the Central Asian states to begin to explore new opportunities and diversify its resources. Hence, this is where Europe could play a vital role in the future.

The war in Ukraine has indeed raised serious doubt about Russia’s continuation as a key player in the region. However, it has not been completely sidelined as Central Asia remains under the sphere of Chinese and Russian influences. Therefore, while there is a need for Europe to increase its visibility in the region, it is important for the EU to first identify where its interests lie and where it can actually make a difference.

Europe’s energy crisis, fueled by the Ukraine war, has imposed significant challenges and has become one of the most debated topics in the EU recently, given that the majority of European energy supplies are provided by Russia. The large leaks detected on the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 pipelines in September 2022 have put enormous pressure on the EU to diversify its energy resources. Norway has become an increasingly vital partner in the EU’s recent pursuit to decrease its reliance on Russia, but the transportation of energy supplies depend on an undersea network of pipelines. In light of the leaks on the Nord Stream pipelines, this now has become increasingly unsafe and imposed another front of security challenges for the EU. As such, Central Asia, with its natural resources, could potentially play an important role in Europe’s energy diversification endeavour. Yet, major infrastructure hurdles obstruct the connection of the rich energy resources of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to Europe.

There is, however, a growing interest from the Central Asian states to deepen cooperation with the EU. More recently, in their first regional high-level meeting in Astana, held on 27 October 2022, the EU and the five Central Asian leaders reiterated their intention to foster stronger cooperation based on shared values and mutual interests. In particular, they highlighted the importance for sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries.

Cooperation between the EU and Central Asia has thus become more relevant than ever. This became more evident following the outcome of the SCO summit in Samarkand. Energy security aside, the EU has significant stakes in Central Asia considering the rapid collapse of its decades-long security architecture and the developments in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the lack of attention over the summit within Europe – which gained more traction internationally – raises the question what the EU’s next steps will be so as to ensure it does not miss this window of opportunity.

Moreover, while Central Asia is often referred to as one single region, the five Central Asian states have followed very distinct trajectories of development. Kazakhstan’s oil wealth and economic growth accelerated its status to become an upper-middle-income country in 2006. To date, there have been political transformations and modest democratic reforms. Yet, recently some bold decisions were taken to reshape the political sphere, including leaving behind the ‘super-presidential’ system and to start decentralising power, to embark on more democratic avenues in the long-term. Additionally, Roman Vassilenko, the Deputy Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan, urged for an enhanced cooperation between the EU and Central Asia in light of the current geopolitical landscape.

Similarly, in Uzbekistan a series of internal reforms were pushed through, with various degrees of success. In 2019 the Economist named Uzbekistan as the “country of the year” arguing that no other country has advanced as far as Tashkent in terms of economic and other reforms that year. Likewise, in 2020 the World Bank placed Uzbekistan among the world’s top 20 for most improved economies. There have also been some positive developments on the political front, as reflected for instance in the increased visibility of the parliament and in the decision to appoint a woman as the chairperson of the Senate for the first time. Yet, further democratic progress will need to be made. An important development in EU-Uzbekistan relations has been Uzbekistan’s successful adherence to the GSP+ scheme in 2021. Uzbekistan’s former minister of foreign affairs, Abdulaziz Kamilov, expressed his gratitude for the increasing cooperation with Europe over the last years and further acknowledged the EU as a vital partner for supporting democratic reforms in Uzbekistan.

Turkmenistan’s recent leadership change has taken action towards further transitioning the country into a market economy, while maintaining tight state control. Despite the region’s complex political reality and the need to speed up the democratic transitioning process, the country holds great potential for economic development and growth. In addition, during their latest meeting in May 2022, Turkmenistan’s new President Serdar Berdimuhamedov and Terhi Hakala, the EU Special Representative for Central Asia, agreed to foster a ‘fruitful partnership’ and expand EU-Turkmenistan relations into new areas of cooperation.

Also Tajikistan has identified the EU as one of the country’s most important partners. Tajikistan’s civil war, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, has hampered its political and economic developments. Although the lower-income country somewhat managed to recover, it continues to struggle to overcome its weakened economic development and political unrest.

Kyrgyzstan has known a history of violent protests against the government followed by a slow economic growth over the past decade. The political unrest and the growing public dissatisfaction have intensified in recent years. Yet, Kyrgyzstan is still continuing its path along the democratic political landscape.

In this context, while regionalisation and closer cooperation among the five former-Soviet states will be essential, the EU should not only engage the Central Asian states at the regional level, but also pursue policies and provide support directly targeted at addressing specific sectors or issues in the different states, or by clustering them. This would require the EU to create the space for the Central Asian states to identify areas of key importance to them in their cooperation and align their interests and development paths. On the other hand, these differences also increase the need to strengthen regional cooperation. This is where the EU would be able to play a significant role in setting up relevant structures and mechanisms to support the Central Asian states, especially given the current shift by some states – most notably Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan – away from Russia. Here, regional cooperation is vital as it allows the Central Asian states to address their regional vulnerabilities, to boost their economic and political potential and perhaps most importantly, to manage their path to independence.

Another quintessential aspect to consider is the younger generation. In their 2020 Comprehensive Research Review, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) highlighted the rapid growth in the young population across Central Asia. In 2020, the region’s total population was 16.55 million, in which the young people accounted for 24.1%. This younger generation is expected to continue to grow, surpassing the older generation across Central Asia in the following decades, as is reflected in the World Population Prospect 2022 published by the United Nations Economic and Social Affairs (UNESA). Taking this into account, the EU should increase its level of engagement with civil society, in particular by reaching out to the younger generations. An increased focus on education and youth programmes would be an effective approach, raising awareness, building capacity and allowing them to take part in and drive regional change. Young people are central for change due to their flexibility, ability to adapt and critical eye on the future. Investing in long-term projects including these generations will be key to fostering a closer future relationship between the EU and Central Asia, strengthening dialogue and mutual understanding, increasing alignment in terms of values, as well as cooperation in terms of good governance, human rights and the rule of law.

On the security front the EU has clear concerns, particularly related to Afghanistan following the Taliban’s return to power. As the EU’s security competence lies with its member states, the EU has limited authority in this field and can make less of an impact. What the EU can do is to utilise the EU-Central Asia High-Level Political and Security Dialogue as an important tool for dialogue and cooperation. It could potentially expand its scope and include countries from the Eastern Partnership or even stretch it further to for instance Japan and India. As a member of the SCO, India already has a foothold in the region and has also strengthened its relationship with Europe in the last decade. Japan is one of the long-standing and consistent external partners of Central Asia, but its role has been overshadowed by China and Russia. For decades, Tokyo has provided support for regional progress, in particular through its ‘Central Asia Plus Japan Dialogue’. On another note, especially for Tokyo it could be seen as a strategic interest from an extended Indo-Pacific perspective.

Overall, the SCO summit in Samarkand was an important reminder of Central Asia’s role in geopolitics. It should serve as a wake-up call for Europe to fully acknowledge the potential of the region and to closely assess how the EU wishes to shape its future engagements in Central Asia and lift its cooperation to the next level. Now may be the right time to act.

Author: Simmi Saini, EIAS Junior Researcher

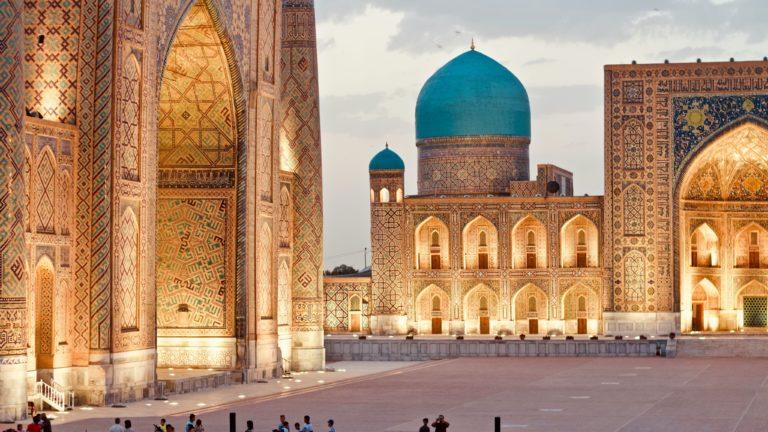

Photo Credits: Unsplash